A bit of context

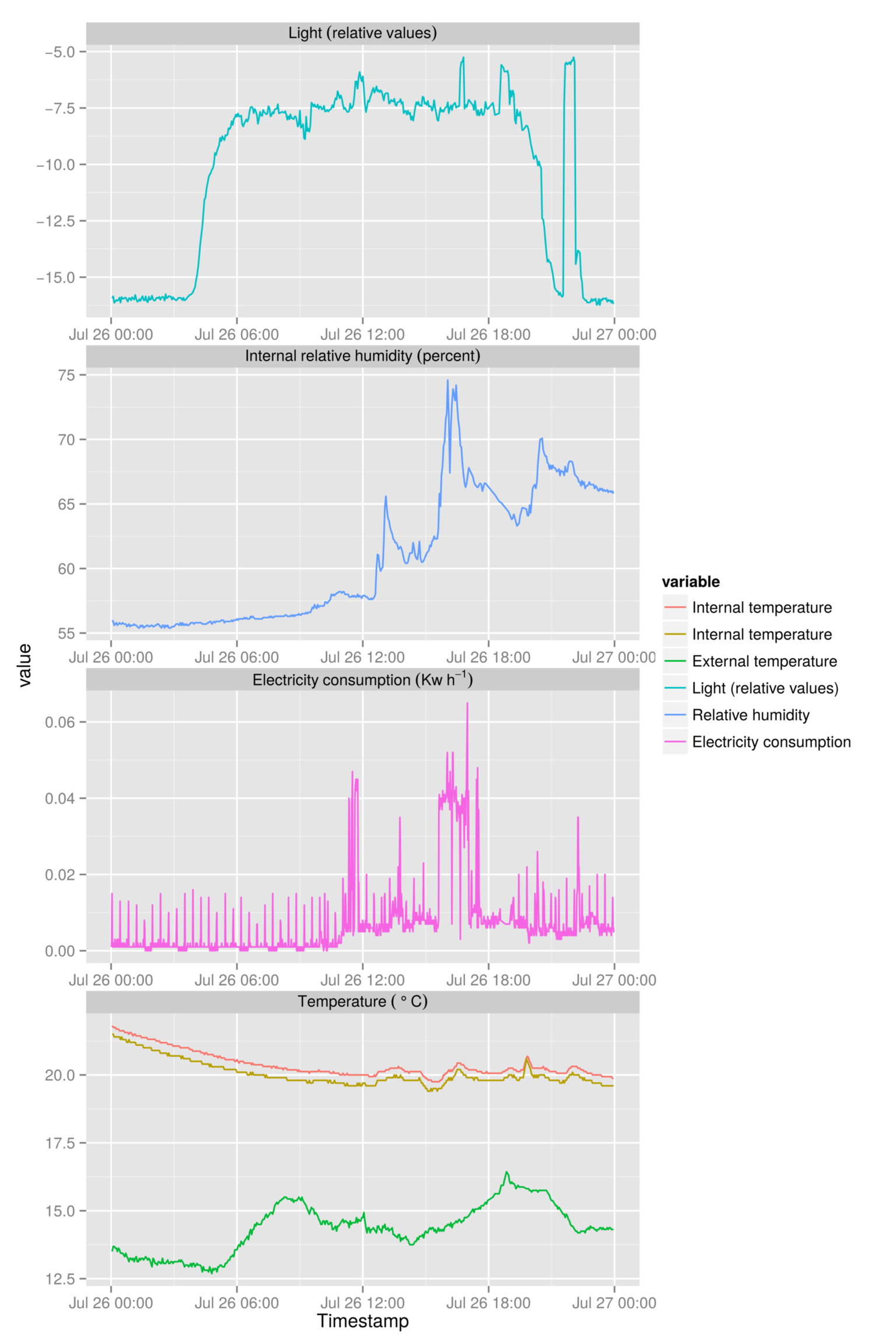

I’ve been playing a lot with raspberry pis over the last couple of years. I’m now the proud owner of an original Raspberry Pi B, A, two A+s, and a brand spanking new Pi 2. Currently I have one sitting next to my electricity meter reading LED pulses from the meter, charting my electricity consumption, and a second running an external and internal temperature sensor, light, and humidity sensors. The data is then pushed to an online server and postgres database, so that I can get access to it wherever I am.

Plots from a raspberry pi driven environmental sensor linked to an online postgres server.

After a conversation with some other researchers at a conference recently, I’ve started to put some thought into how I can use raspberry pis or arduinos to measure environmental variables like temperature, humidity, light intensity, and soil moisture content in the field. Soil moisture content is an interesting one, because there are lots of questions that can be answered with real-time (or near real-time) soil moisture sensing.

One of the applications is in agroforestry research, which was partly the subject of my PhD and subsequent post-doctoral research. Agroforestry systems are combinations of trees with agricultural practices, be it arable of pastoral. In the case of arable, the interaction between trees and crops can have an influence on soil moisture content, and there are a number of other questions that might be answered in similar fields by the deployment of cheap soil moisture sensors and arduinos.

There are of course proprietary soil moisture sensors, but they are much more expensive; whilst perhaps not prohibitive for the odd one or two sensors, deploying a network of many tens, or a hundred or so sensors would certainly be out of the question for most research budgets.

Developing an arduino powered soil moisture sensor

The internet being what it is, there are already a host of resources available online for environmental scientists. One of the most promising I came across is the Van der Leer Vineyard who have created their own autonomous viticulture monitoring system called Vinduino, and even published a conference paper on the subject.

There’s a great alternative to their design of soil moisture sensor using 3D printed parts here making use of 35 mm hair curlers, and a 3D printed top and base to perfectly space stainless steel M3 studding to act as electrodes.

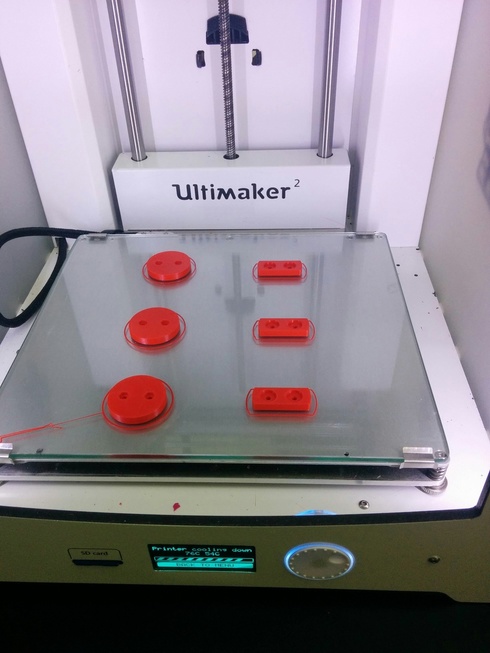

This is the design that I’m going to play with, so over the last week I have been assembling components with the help of @MCeeP who was kind enough to print the caps for my first three sensors.

Parts freshly extruded on the printer.

I’m just waiting for some new studding to arrive so that I can finish the construction and cast the sensor from gypsum, which is cheaply available as ‘plaster of Paris’.

Starting to assemble a sensor before casting with gypsum.

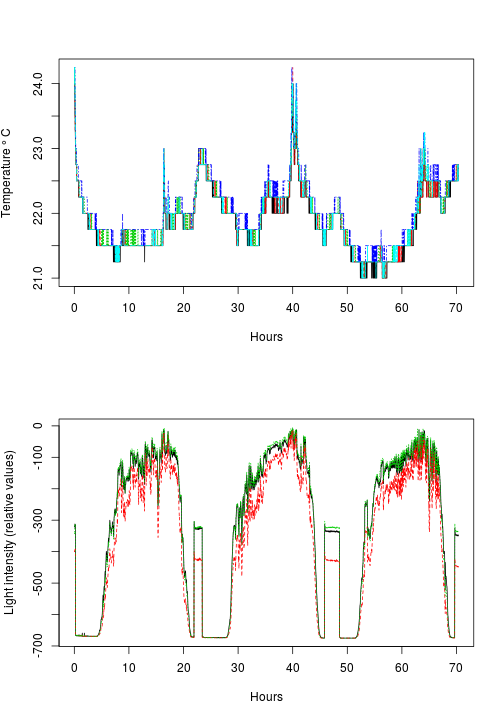

In the meantime, I have also been doing some experiments to work out how long I will be able to run an Arduino in the field on battery power. So far I have been testing a setup with 5 ds18b20 temperature sensors, and three light dependent resistors (LDRs) acting as light sensors running off a 10,000 mAh lithium ion battery pack designed for re-charging mobile phones.

With a measurement frequency of once every minute, and logging values to a microSD card, though not at present with a real time clock unit, on an arduino Uno, I’ve managed to get around 70 hours of life from the arduino, without any special effort to save battery power

Field based readings are likely to be much less frequent, so even with a relatively small battery I anticipate getting several days worth of readings.